Lawmakers see little action for pesticides near schools

Iowa state Sen. Bill Dotzler (D-Waterloo) has traveled across Iowa’s country roads on his bicycle while training and riding for RAGBRAI. On these rides, he pays attention to farmers spraying pesticides in fields along his routes.

“I’ve been out on the roads where you can see sprayers in high winds situations. You know you kind of pedal as fast as you can so you don’t get hit with it,” he said.

Sen. Rich Taylor (D-Mount Pleasant), a member of the Senate Agriculture Committee, said he has been wanting to introduce legislation that would limit the effects of overspraying by addressing conditions and amount of feet when spraying pesticides. “We haven’t got much done on it because there is a lot of resistance from the farming community to regulate how they take care of their cropland,” he said.

Although Taylor wants to introduce legislation that could limit overspraying, he has not moved forward with legislative action because of the interest of farming community. “There are a lot of things we can do, but we cannot force our farmers to not save their crops, but we need to make sure they are doing it in a smart way that is not hurting other people too,” Taylor said.

“We can’t have them overspraying onto people living their normal life, whether it be school kids or citizens out enjoying the park,” he said about people spraying pesticides. “We’re going to have to look at this a lot more seriously.”

State Ag. Committee Chairman, Dan Zumbach (R-Ryan) said regulating spray drift has not been addressed in the legislature because it is not a widespread problem. “That’s why it doesn’t come up as something that needs to be solved. It appears that it is not a widespread problem,” he said.

Zumbach, a farmer and farm owner who applies pesticides, thinks buffer zones are not necessary if pesticides are applied responsibly and as directed on the label by applicators. “It’s not a topic that has come up and it’s probably not a topic that I’m interested in today. I’m more interested in each property owner being responsible for themselves,” he said.

“I think all chemicals need to be applied as directed. And that the applicator needs to understand this responsibility in application. When used properly they are considered safe by government agencies, when used properly” Zumbach said.

State Rep. Sandy Salmon (R-Janesville) acknowledges harmful effects from pesticides but considers any new law unnecessary because a label on pesticide containers includes legal restrictions on using the chemicals. “I know they can have harmful effects on people depending on how they are handled,” she said.

“I believe the guidelines found in the law provide more flexibility to address the harmful effects people could experience than a buffer zone would,” Salmon said.

Pesticides are used often in Iowa, a state known for agriculture, and drift comes along with that. Public buildings and residential areas fall close to agricultural land because of high demand for agriculture in Iowa.

About nine out of 10, or 89.6 percent, of Iowa pre-kindergarten-through-12th grade school buildings are within 2,000 feet of crop land, the Science in the Media project at the University of Northern Iowa reports. That’s 1,183 of 1,321 school buildings. IowaWatch is a partner of Science in the Media, a program that produces journalistic reports on science-related topics and trains college and high school student journalists to do science reporting.

The distance of 2,000 feet is based on a 2006 study by researchers led by M. H. Ward of the National Institutes of Health, who found an increased risk of potentially harmful pesticide spray drift from croplands at that proximity. To put 2,000 feet into perspective, the distance is about three city blocks in Iowa.

Pesticide spray drift’s effects are not limited to bikers who ride by a farm field. Young people and community members are affected as well. Drift could be especially harmful to young people who attend schools that are adjacent to or near Iowa’s croplands.

Ninety-five percent of Iowa’s corn and soybean planted acres are treated with pesticides and herbicides, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service.

According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, “A pesticide is any substance used to kill, repel or control certain forms of plant or animal life that are considered to be pests.” There are various types of pesticides including herbicides that are used for getting rid of unwanted plant and animal life.

Dotzler said the harm pesticides can cause humans has been overlooked for too long in Iowa. “It is definitely something we should be more concerned about because if we’re talking about pesticides or herbicides, those things can accumulate, especially in young grades when you have the most thinkgrowth going on. Those chemicals can be absorbed by the body and they stay there,” Dotzler said.

Dotzler has been a legislator for 22 sessions and does not remember his fellow legislators addressing pesticide spray drift near Iowa schools.

Dotzler said an incremental legislative approach might be effective. “I think in order to get something done, you have to do it in little steps, and I think wind speed and restrictions on how windy it is when spraying, especially in an area where you would call a buffer zone near schools would be a good place to start,” Dotzler said.

Iowa Sen. David Johnson (I-Ocheyedan), a former member of the Agricultural Committee and former dairy herdsman, said he has heard concerns from rural residents who were worried about spray drift. “I got a couple of calls from people who live on acreages. They were concerned about drift and overshooting from fields and dropping chemicals on the house and actually on them,” Johnson said.

Reporters tried to contact agriculture committee senate members Waylon Brown (R-Ansgar), Kevin Kinney (R-Oxford), Amanda Ragan (D-Mason City), Rita Hart (R-Wheatland) and Walt Rodgers (R-Cedar Falls) but did not receive a response.

According to a study by the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, 41 states, including all of those in the agricultural Midwest, have no regulations requiring buffer zones around public buildings to protect the people from potential pesticide drift from nearby farm fields. California put new rules in place in January 2018. It was the first of nine U.S. states to regulate state wide buffer zones around schools this year, according to the Pesticide Action Network.

The buffer zones in California apply to all residential and public areas where people could be harmed. “Notification on spraying is a critically important piece of the program from our perspective. If people aren’t aware that spraying is occuring, they aren’t able to protect themselves in any way,” Kristin Schafer, executive director at the Pesticide Action Network, said.

The California regulation requires a quarter mile buffer between cropland pesticide spraying and public school grounds.

“One of the things we found through our own ground research using our drift catching equipment is that there is definitely drift beyond that quarter mile buffer for certain chemicals,” Schafer said. “The reality is that chemicals can be moving more than that quarter mile and into buildings where people and especially children are very vulnerable to that exposure.”

The Pesticide Action Network says evidence exists that links pesticide spray drift to children’s health issues. “There are studies showing that exposure to chemicals during pregnancy or the first few years of life is linked to increased of cancer, ADHD, autism, learning disabilities, et cetera,” Kristin Schafer, Executive Director at the Pesticide Action Network, said.

The Iowa Code provisions in chapter 206 and the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) allow pesticide and herbicide use through regulations and labeling.

A pesticide cannot be registered under the act unless the applicant can prove that it “will not generally cause unreasonable adverse effects on the environment.’’ This means the chemical cannot pose an unreasonable risk to humans, including dietary risk or the environment in any form.

The Iowa Farm Bureau suggests that current practices are sufficient to protecting students at schools near farm fields from spray drift. “Clearly, farmers are very conscious of the conditions that can contribute to drift, and are already avoid spraying close to schools when these conditions exist,” Laurie Johns, Iowa Farm Bureau public relations manager, said.

Mommsen rents a family farm in Clinton Iowa, called Mommsen Farms. He manually sprays his farm fields twice during the later half of April and during the month of May. He applies the herbicides Roundup, Balance Pro and Authority.

Before applying pesticides and herbicides, Mommsen does not notify people in nearby houses or public buildings. He said buffer zones would not be implemented in Iowa, calling them redundant because application and safety precautions of spraying are addressed by the label included on the chemical container. “If you are following the label, you should not be concerned at all,” Mommsen said.

Mommsen said he follows the protocol provided by the chemical companies, taking precaution when guided to and holding back from spraying when instructed to. Mommsen said he is cautious of the nearby houses, especially when winds are high. “Around my farm here, I’ve got houses. I’m very careful never to be spraying so it’s spraying onto my neighbor,” Mommsen said.

Taylor said that instead of implementing buffer zones, legislators are meeting and talking about restricting the use of pesticides in certain weather conditions and changing the way farmers apply. “What we need to do is make it that they wouldn’t be allowed to do it if the wind speed is too high or in a certain direction that would affect the public. We also need to look at the way that they apply because there are things that they can do to limit the overspray even if they are close to schools,” Taylor said.

Iowa representative and agriculture chair member Lee Hein (R-Monticello) said he doesn’t find that spray drift could be an issue with a 2,000 foot distance determined by the 2006 study by the National Institute of Health. “You’re talking 2,000 foot. That’s almost one-third of a mile. That’s quite a distance for drift. It would take ideal conditions. I just find that hard to believe that is a health issue at that distance,” he said.

“Let’s flip the table. If a farmer has been farming the property, and all of a sudden a school goes up beside him, should he be forced to take land out of production just because the school has showed up?” Hein asked. “I think it would probably fall under the requirements of the school to buy that buffer zone from the farmer, to maintain the buffer zone,” he said.

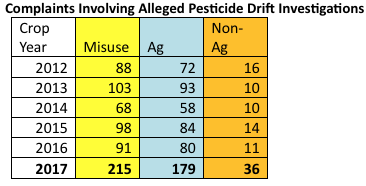

As for cases involving pesticide drift and schools, Iowa’s Pesticide Bureau staff has reviewed records from Crop Year 2006 to Crop Year 2017 (10/1/2006 to 9/30/2017), over this period, only one complaint has been documented to include allegations of pesticide drift from a neighboring property to school’s grounds. The outcome of this investigation indicates that no pesticide application took place because the complainant mistakenly thought that anhydrous ammonia was a pesticide. For this reason, the complaint was dismissed.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login