For girls, women with ADHD, health system providing woeful deficit of attention

When one thinks of Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder, one may think of a child, most likely a young boy, who is hyperactive and loud. These children are easy to spot in a classroom, always talking, not paying attention and are being disruptive.

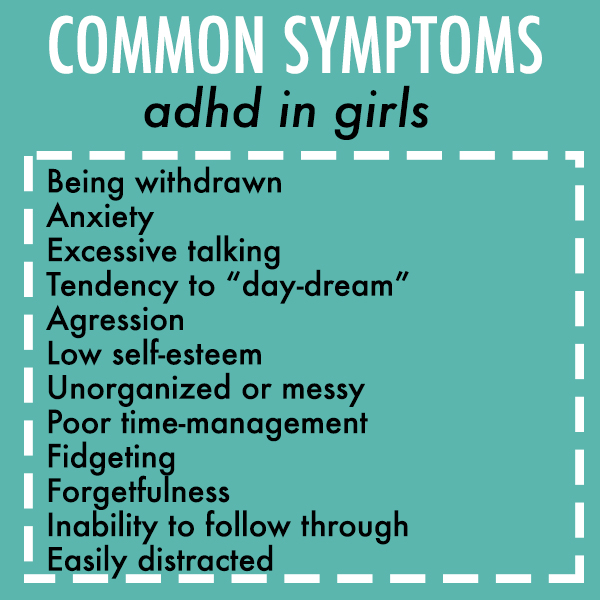

When ADHD is diagnosed, the symptoms most commonly searched for or questioned about are these stereotypical symptoms, but these are often not the same symptoms exhibited by girls with ADHD. Some girls do exhibit these symptoms that are most commonly found in boys, but most do not, leaving many girls undiagnosed and untreated.

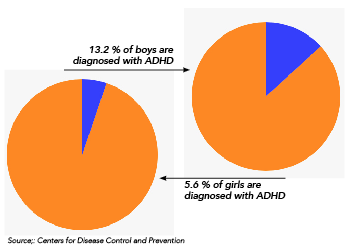

The profile for girls with ADHD is scattered and hard to pinpoint, unlike their male counterparts, which may account or contribute to the fact that boys are diagnosed at a rate five times higher than girls.

Because symptoms in girls are harder to spot and often do not fit the stereotypical profile of someone having ADHD, there is a skewed perception that boys are more likely to have ADHD. However, ADHD is an “equal-opportunity disorder” meaning that it has the same likelihood to occur in either gender, but in girls, the disorder is not diagnosed or treated as much or in the same order.

“In my experience, girls and women are often underdiagnosed,” said Marc Groen, who has worked 15 years as a school psychologist and is currently working with students at Cedar Falls Schools. “I’ve known hundreds of boys diagnosed with ADHD, but only a handful of girls.”

While ADHD can be categorized into three types — inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive and combined — ADHD in girls can manifest itself in a multitude of different ways. This was not recognized by the health community until relatively recent times. This has long left women and girls calamitously underdiagnosed, living life with no treatment and over-compensating for the skills they lack, painting a seemingly pretty picture with messy and complicated personal undertones.

While ADHD can be categorized into three types — inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive and combined — ADHD in girls can manifest itself in a multitude of different ways. This was not recognized by the health community until relatively recent times. This has long left women and girls calamitously underdiagnosed, living life with no treatment and over-compensating for the skills they lack, painting a seemingly pretty picture with messy and complicated personal undertones.

While some girls do display the stereotypical symptoms most often seen in boys, the majority of girls with undiagnosed ADHD are hiding in plain sight due to it’s difficulty to decipher. “People imagine little boys bouncing off the walls and think: That’s what ADHD looks like, and if this girl doesn’t look like that then she doesn’t have ADHD,” said Dr. Patricia Quinn, director and co-founder of the National Resource Center for Girls and Women with ADHD, in an article for Childmind.org.

Common behaviors of girls with ADHD include the Daydreamer: inattentive in class, seemingly focused with an internal thought bubble hundreds of miles away, forgetful, disorganized, anxious and easily overwhelmed, probably gazing out the window or picking at her fingernails; the Chatty Kathy: a bubble of socialization, interruption, having difficulty organizing her thoughts when telling a story, using a silly facade to mask underlying issues; the Smart Girl: seemingly sharp-witted, often masking concentration and organization problems until later in life when expectations are more demanding; and the more typical Tomboy: show-off, hyperactive, always jumping from one thing to the next, always trying to impress someone.

In today’s society, girls face an enormous pressure to conform to unreasonable expectations. Girls are trained by every aspect of modern life to mask mistakes and and hide imperfections, striving to fill a certain mold of what a woman should look and act like in our world. Girls with ADHD are ostracized and stigmatized because of the traditionally “masculine” nature of symptoms like messiness, bossiness and hyperactivity that ADHD presents, causing girls to be ashamed and feel the need to hide and internalize their struggles with simple everyday life. While boys are treated, girls are scolded.

“I’ve observed that girls may display symptoms differently, or teachers treat them differently from boys” Groen said. “For example, some boys may be more disruptive or hyperactive, while girls may have more difficulty with inattention or executive functioning deficits. Typically, students that are more disruptive to the learning environment will be more closely monitored by their teachers.”

The difference in symptoms does not make ADHD in a girl any less valid or undeserving of treatment as the disorder in a boy, a message still attempting to permeate the minds of not only the general public, but the health community as well.

ADHD going undiagnosed in girls can lead to a variety of varying physical and mental health problems in adolescence or later life. “While research of ADHD in women continues to lag behind that in adult males, many clinicians are finding significant concerns and co-existing conditions in women with ADHD. Compulsive overeating, alcohol abuse and chronic sleep deprivation may be present in women with ADHD” reads the National Resource on ADHD’s website.

According to mental health research from the National Institutes of Health published in the American Psychological Association, boys are more likely to outwardly exhibit signs of aggression and hyperactivity that accompany ADHD, while girls turn their frustrations inside. This was also noted in a 2012 study by Stephen Hinshaw, PhD. “ADHD in girls and women carries a particularly high risk of internalizing, and even self-harmful behavior patterns,” Hinshaw said. “We know that girls with ADHD-combined are more likely to be impulsive and have less control over their actions, which could explain these distressing findings.”

“I’m stupid,” “I can’t do anything right,” “It’s all my fault” are often common mantras within the heads of girls and women with ADHD. Behind the facades of false proficiency, many girls find themselves crumbling under pressure to succeed, often silently, due to the common stigma that ADHD is a “boy’s” problem.

These self-convicting tendencies lead to years of low-self esteem and often times self-destructive behavior, eating disorders, depression and anxiety. This becomes a heightened problem during adolescence when hormones fluctuate, causing girls to become moody and reactive, and increasing their risks for other mental health problems.

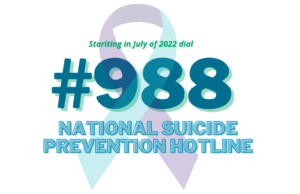

According to a study conducted by Stephen Hinshaw, director of Psychology at the University of California-Berkeley, girls with ADHD have significantly higher chances of self harm or suicide attempts. Of the participants in the study diagnosed with combined ADHD, 51 percent reported self-harming actions like scratching, cutting and burning themselves, and 22 percent reported at least one suicide attempt prior to the 10-year follow up.

For many women who go undiagnosed, symptoms of ADHD like forgetfulness, disorganization, a tendency to blame themselves, and impulsivity are mistaken simply as personality flaws, and they are often labelled as “lazy,” “ditzy” and “absent-minded.”

When the structure of compulsory education disappears and the transition into adulthood begins, women often times find themselves at war with the issues they were once able to suppress in childhood and adolescence, forcing themselves to come to terms with their long-time and overwhelming feelings of inadequacy when tackling responsibilities and relationships.

ADHD misdiagnosis or failure to be diagnosed robs young women of opportunities to be academically successful or receive accommodations and treatment that would help them succeed and overcome their internal struggles. Without proper diagnosis and treatments, girls carry these problems into adult life, where failures become evident and self-accusations become more than common. According to Quinn, “The average age of diagnosis for women with ADHD, who weren’t diagnosed as children, is 36 to 38 years old.”

Groen offered an explanation to the fact that women are often not diagnosed until adulthood, as stated by Quinn. “My best hypothesis is that many young women begin to advocate for themselves with their health care providers as they approach adulthood,” Groen said. “When they begin to share their own health concerns, more of these concerns become apparent.”

Seemingly intelligent and functional women and girls are often disregarded as candidates for ADHD diagnoses due to their abilities to compensate for or mask their symptoms much longer than boys Many are often misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder, anxiety and depression.

So why are girls not being diagnosed?

The current diagnoses process in the state of Iowa includes evaluation from parents, family, teachers and health professionals. When a child is suspected to have ADHD by parents or a pediatrician, often times the first step is a written evaluation from teachers or educators that the child has frequent contact with.

According to the Psychiatric Associates of Iowa City, “Health care providers and educators may also observe and evaluate the child.” This means a portion of the weight of the evaluation is based on the child in a classroom setting and being evaluated by someone who is not a health professional using biased criteria.

“Young children that are the first to be diagnosed are often those with more difficulty managing hyperactive symptoms,” Groen said. “Oftentimes, these students will be the first identified by teachers and parents as they devote a large amount of time and effort helping them to manage their symptoms and making learning gains.”

Obviously, the quiet girl in the corner chewing her nails and looking out the window would not attract the same attention or scream ADHD as the disobedient boy who cannot seem to keep his mouth shut or follow simple directions.

“However, referral bias is a problem, in that females with ADHD are less likely to be referred for treatment than males with ADHD,” said JJ Rucklidge of the Department of Psychology at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, in a journal published in the Psychiatric Clinics of America. Besides the obvious fact that symptoms are just not noticed, the diagnosis process for ADHD does not account for the varying exhibitions of the disorder, catering only to the stereotypical attributes most often found in young boys.

There has been a recent push by many health professionals and researchers for new criteria of diagnosing ADHD, including gender-based criteria. According to experts, future research that includes equal representation of boys and girls should also be conducted to form diagnoses processes that cater to more than just one profile of children with ADHD. “More research regarding gender differences, child development and public awareness is needed,” Groen said.

Despite the growing dire need for modification, the flawed standard continues to be used to diagnose Attention Deficit-Hyperactive Disorder. The current system is failing girls and women, leaving them wrestling themselves inside their minds.

(For mental health week, we published a couple more articles on mental health awareness, stress and different types of mental health problems, other similar topics. To read them and past articles on the issue, click right here or type in “mental health” in the search bar at the top right corner of our website.)

Check out a video about stomping out bullying at the high school below!

You must be logged in to post a comment Login